Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...Categories

- Sales

- Games and Apps

- Categories

- Body Systems

- Adrenal Support

- Blood Sugar Support

- Bowels

- Circulatory System

- Digestive Health

- Digestive System

- Endocrine System

- Energy/Stamina

- Eyes

- Female Health

- Immune System

- Integumentary System

- Intestines

- Liver/Gallbladder/Pancreas

- Lymphatic System

- Male Health

- Male/Female Support - Intimacy

- Male/Female Support - Reproduction

- Mood/Emotional Support

- Muscular System

- Nervous System

- Oral Health

- Overall Good Health

- Reproductive System

- Respiratory System

- Skeletal System

- Sleep/Relaxation

- Stomach

- Stress/Anxiety

- Thyroid Support

- Urinary System

- Weight Management

- Brands

Join Our Newsletter

A Brief History of Tea

The origins of tea are steeped in legend (sorry.) and hard to trace. The written characters used in ancient Chinese texts have evolved with the ages in both meaning and form, so modern scholars do a lot of guessing when determining whether ancient texts are actually referencing tea or something else entirely. Although the factualities behind tea’s discovery may never be known, two primary legends have endured.

![]()

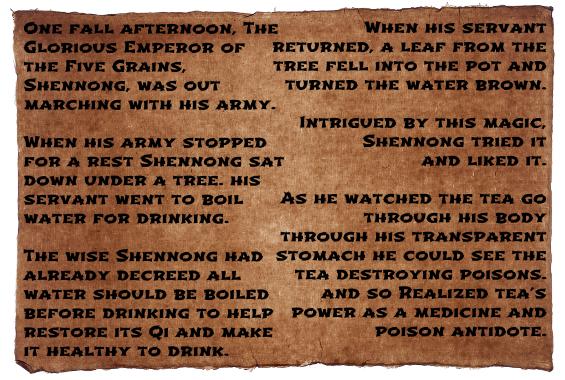

The Chinese legend credits the discovery of tea to a legendary/mythical Emperor named Shennong (Chinese: 神农). Shennong was one of the Three Sovereigns, a group of demigods who lived around 2800 BCE. The Three Sovereigns used their magical powers to help their subjects and teach them essential skills. Two of Shennong’s most important teachings were agriculture and herbal medicine. Besides having discovered tea, Shennong is credited with things like the invention of the hoe, plow, axe, Chinese calendar and acupuncture. Shennong is said to have personally tried hundreds of plants, including poisons, to determine their effects. Some versions claim he had a transparent stomach so he could actually watch what the plants did to his body. The Shennong legend goes something like this:

![]()

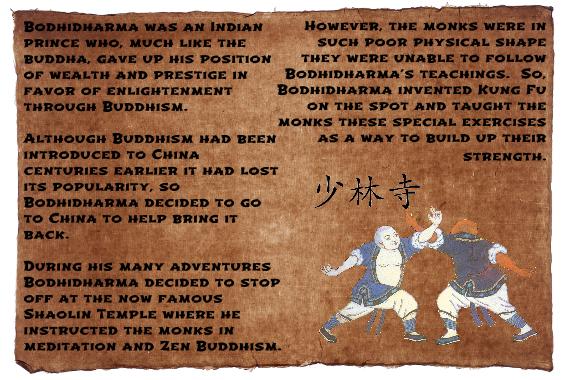

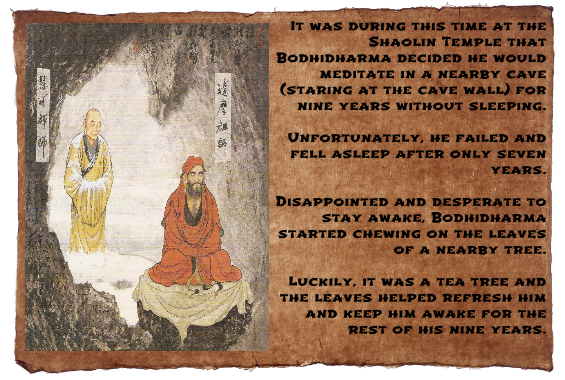

The history of tea in Japan is intimately tied to Buddhism. It was Buddhist monks who first brought tea back from China circa 800 CE. Because of tea’s natural caffeine content it helped the monks stay awake during their long meditations and it was an instant hit. Later, after Tokugawa Ieyasu finished unifying Japan circa 1600, the now-idle samurai class adopted a renaissance aesthetic, where great samurai were now judged as much by their poetry, calligraphy and flower-arranging skills as they were their skills with the sword. It was during this time the samurai class embraced Zen Buddhism and in particular the Japanese Tea Ceremony. The Japanese legend, not surprisingly then, credits a Buddhist monk named Bodhidharma (bo-dee-dar-ma) with the discovery of tea. The Bodhidharma legend goes something like this:

It’s highly unlikely either of these legends comes anywhere close to the truth. Shennong would have lived almost 5000 years ago, and his transparent stomach story is clearly myth, regardless of whether the person of Shennong actually ever existed. Bodhidharma was likely real, but no actual written record was ever made of his travels. His stories are all woven with Paul Bunyan-like folk telling, and regardless of if he ever made it to the Shaolin Temple he would have been tramping around China circa 450 CE. Tea was already part of Chinese daily life (as a medicine) by this time, with written references as early as 290 CE, so the timing is clearly off. Many earlier possible references to tea exist in Chinese texts, with one as early as 500 BCE, but the changing nature of Chinese characters makes it impossible to verify these earlier writings as being actual tea references or not.

Most likely tea was discovered just like any other food source, through trial-and-error by some unnamed ancestor in our distant past. In her book, Tea: The Drink that Changed the World, Laura Martin states, “K. Jelinek, editor of the Illustrated Encyclopedia of Prehistoric Man (1978), suggests that the first tea was consumed by the time of the early Paleolithic Period (about five hundred thousand years ago.) Archeological evidence from that period indicates that leaves of Camellia sinensis ... were placed in boiling water by Homo erectus in the area that is now China. The fact that the tea plant is indigenous to many parts of China supports Jelinek’s claim.”

![]()

Fourth and fifth century Chinese tea is not what tea is today. Tea was not consumed as a beverage but strictly as a medicine made from boiling the raw leaves in water. It was bitter and hard to swallow. It would take many years before tea growers started processing the leaves to improve the flavor.

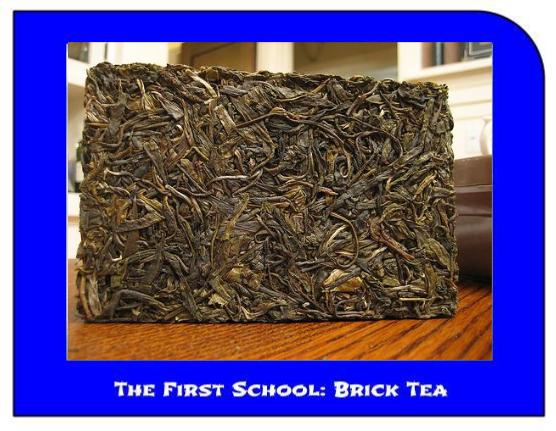

It was during the late Northern Wei Dynasty (386-535 CE) that growers first started processing the leaves. This is referred to as the first “school” or phase of tea. The leaves were gathered and then pressed or beaten into bricks which were then baked or roasted until the leaves turned a reddish-brown. To make the tea, small chunks would be broken off the brick, ground into a powder and then boiled in water for several minutes.

Picture Credit: Jason Fasi via wikipedia.com

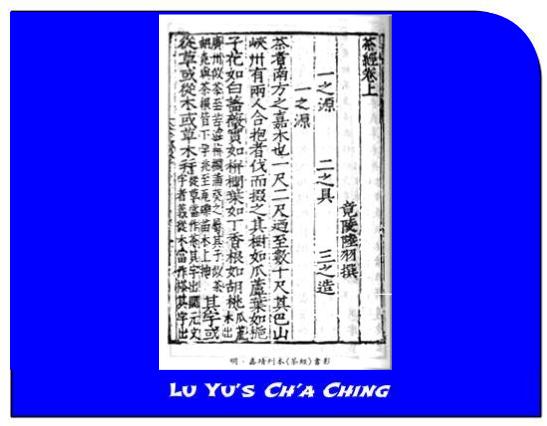

During this time tea was becoming more and more popular, but its availability remained limited due to the limited information on how to actually grow, harvest, and process the leaves. At this time all information was passed on orally. Then, in 780, Lu Yu published his famous Ch’a Ching where he detailed every aspect of tea cultivation, including his famous “Rules for Drinking Tea.” The book was the first time the common man had access to the secrets of growing tea and as expected contributed not only to tea’s popularity but also greatly to its availability.

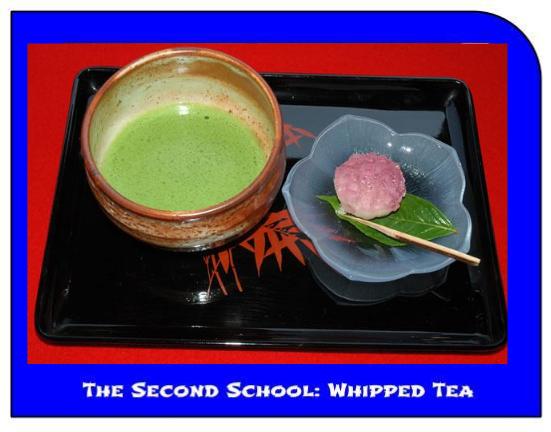

A couple hundred years later, in the eleventh century, Chinese tea growers started processing the leaves in a new way. This is referred to as the second school of tea. Instead of pounding the leaves into a brick, the leaves were steamed, dried out, and then powdered. This powder was then added to boiling water and whipped with a bamboo whisk until foamy. This produced a much better tasting tea and this type of tea (matcha) is still used today in the Japanese Tea Ceremony.

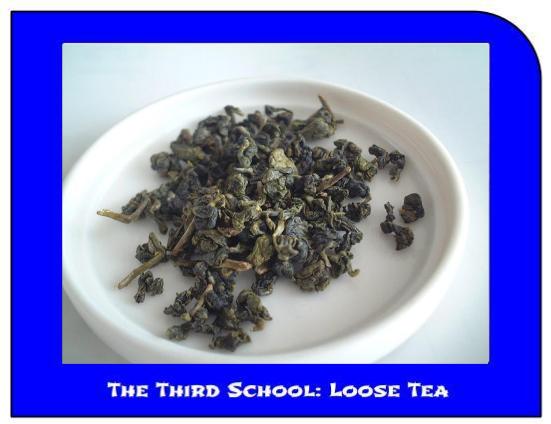

The third school of tea, which we are still in today, began during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644.) This is when tea growers started producing loose leaf teas by first picking, then withering, rolling, oxidizing and then drying the leaves. These loose leaves are then steeped in hot water to produce a smooth, full bodied taste far superior to even whipped tea. The loose leaf process also allowed tea growers to start adding different things to the tea to produce different flavored teas. The most famous and popular of the Ming Dynasty teas is Jasmine Tea.

![]()

The British first started trading with China circa 1650. At this time the Chinese held a worldwide monopoly on tea and kept its cultivation and processing methods a closely guarded state secret. Unfortunately for the British, once they got a taste for tea there was no going back. During these early days of trade the Chinese had no interest in English goods and would only accept silver as payment.

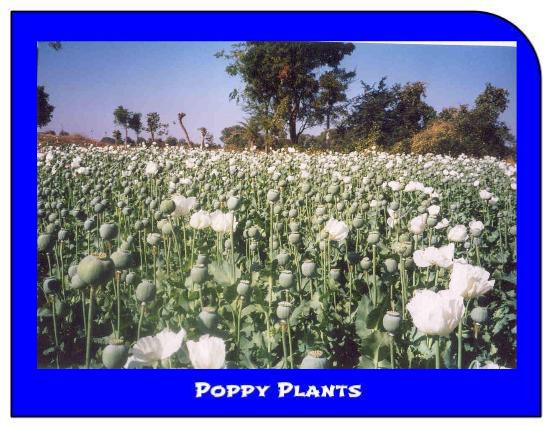

England had to buy its silver on the open market so this left them with a huge trade deficit with China. It also left them on the lookout for something the Chinese would actually buy to help reduce their deficit. Sadly, they found their answer in their newly acquired Indian colony: poppies.

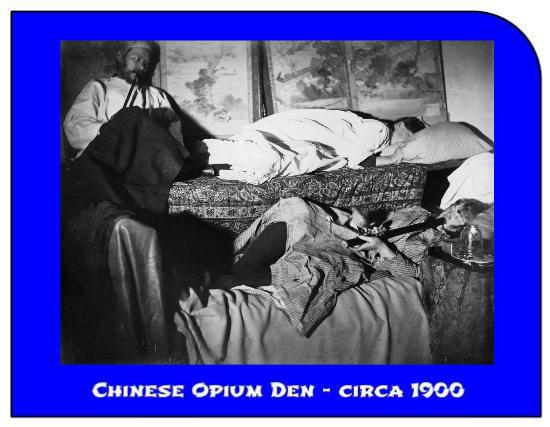

At first the Chinese government tolerated the opium trade because it also increased their own profits as England could now buy more tea. However the situation soon proved devastating for China as more and more of its population became addicted. The demand for opium grew so high that the flow of silver soon turned the other way, out of China and back to England.

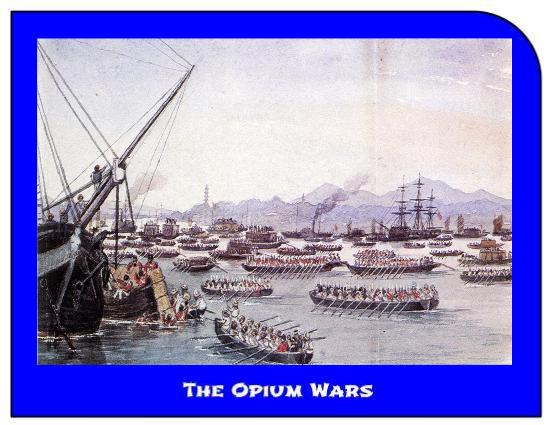

In June of 1839 the Chinese Emperor finally had enough and banned opium. The Chinese closed the port at Canton and forced the British ships to surrender all their opium and swear to never trade opium in China again, under penalty of death. The captains were then freed and trade was resumed.

One year later, in June of 1840 the British attacked. Although the Chinese had invented gunpowder, they had never really perfected its use militarily and were soundly trounced by the superior British cannons and rifles. And finally in August 1842, fearing the British would capture and kill the Emperor, the Chinese signed the Treaty of Nanking aboard the HMS Cornwallis. Not only did this treaty force China to resume trading opium, China was forced to pay for British war costs and the opium it had seized previously in Canton. This is also when China was forced to cede Hong Kong to Britain “in perpetuity.”

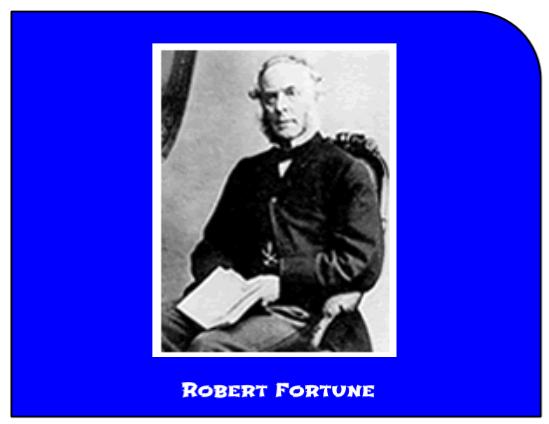

Now, with greater access to China, in 1843 Scottish botanist Robert Fortune went to collect and document new and unknown plants indigenous to China. During this trip he was the first Westerner to observe how the Chinese processed their tea leaves.

For decades the British had known a native tea tree grew in India but struggled to make any quality tea. So, in 1848 the East India Company hired Fortune to return to China, this time to find and bring back the best specimens of tea trees to grow in India. Fortune was hugely successful and brought back some twenty thousand specimens, and more importantly he also acquired the tools and materials needed to process the tea leaves into quality tea. And, as these things go, by 1888 Indian tea plantations were outproducing their Chinese counterparts.

Having won the first war so easily, and hungry for even greater trade access, in 1856 the British attacked again and again easily won. In 1858 China signed the Treaty of Tientsin which opened up even more ports and allowed in Christian missionaries, and eventually lead to the legalization of opium in China, further increasing British profits and further addicting the Chinese people. This was, in a very real sense, the beginning of the end for Imperial China.

Picture Credit: Louis Philippe Lessard via wikipedia.com

“It is a curious circumstance that we grow poppy in our Indian territories to poison the people of China in return for a wholesome beverage which they prepare almost exclusively for us.” - John Barrow, 1836

![]()

No history of tea would be complete without at least a few words about the man whose name has become synonymous with tea. Sir Thomas Lipton was a Scottish grocer and self-made millionaire who wanted to start importing tea to his stores in England. His plan was to undercut the competition by eliminating all the middlemen and growing and importing his own tea.

As fate would have it, about this time (1869) a fungus wiped out all the coffee trees on Sri Lanka (called Ceylon in those days) and completely destroyed the coffee industry there.

In 1890 Lipton was able to buy four of these old coffee plantations for next to nothing. Aided by a man named James Taylor, who had been growing tea in Sri Lanka since 1867, Lipton was able to produce his own tea and sell it to the common folks of England for unprecedented low prices.

Together Lipton and Taylor built the Sri Lankan tea industry, which today stands as the fourth largest producer of tea in the world.